New Era American

Carlos and Rafa Robles

Innovation Studio Founders

Chicago, Illinois

Made in America

Dec 13, 2023

ORIGINS

Who are you, where are you from and where are you going?

Rafa:

I'm Rafa Robles. Since there are two people here, we're gonna have a very similar origin story. We were both born in San Luis Potosi, Mexico – about four hours north of Mexico City.

Carlos is the eldest. We have one younger sister. But Carlos and I are only a year and a half apart, so we're like Irish twins – or Mexican twins? – but we're not twins. We grew up in an upper middle-class environment in Mexico. We were fortunate to learn English at a private school, which became useful when we moved to the US in 2004. I was 12 or 13, Carlos was 13 or 14.

We flew into Chicago undocumented – I guess technically we're still undocumented. Our dad worked at a pizza place in Chicago proper before we moved to the Chicago suburb Palatine, a pretty Republican place.

Moving was a traumatic shift from an upper middle class environment to a basement apartment in Chicago, where we slept on air mattresses. Our mom wanted us to go to a better school. Those suburban schools look like they do in the movies: a football stadium, cheerleaders and tennis courts. We're like, “Holy shit this is amazing and this smells like school!” There's a particular, weird high school smell– an institutional smell.

May I ask why you left?

Carlos:

It’s a combination of bad business choices and insecurity and crime in Mexico. When our parents lost everything, they figured, “Why not start over?”

Rafa:

There was a conversation before we moved about Canada or the US, and we were all like, “Canada?? Why would we go there? The US is amazing!” We had gone to Disney on vacation and we watched the movies. We were definitely propaganda-ed into moving to the US.

Carlos:

The propaganda says this is the land of opportunity: you work hard, you can get by and you can succeed. But we were undocumented kids so very quickly we started to see that this shit is kind of rigged! There was no path for us to get papers – even though we had straight A’s and were captains of the tennis team. A teacher took an interest in us because we played tennis really well. Nobody had ever seen Mexicans play tennis so well in Palatine.

Other things started piercing the propaganda veil. Come college application time, we couldn’t access funding and FAFSA loans. We couldn’t get drivers’ licenses – things compounded.

We had a friend from high school who went to Harvard. He was smart but he also knew how to play the game; he taught us about it. In 2010, we were in community college when he invited us to Harvard. Because we didn’t have papers, we took a train, not a plane.

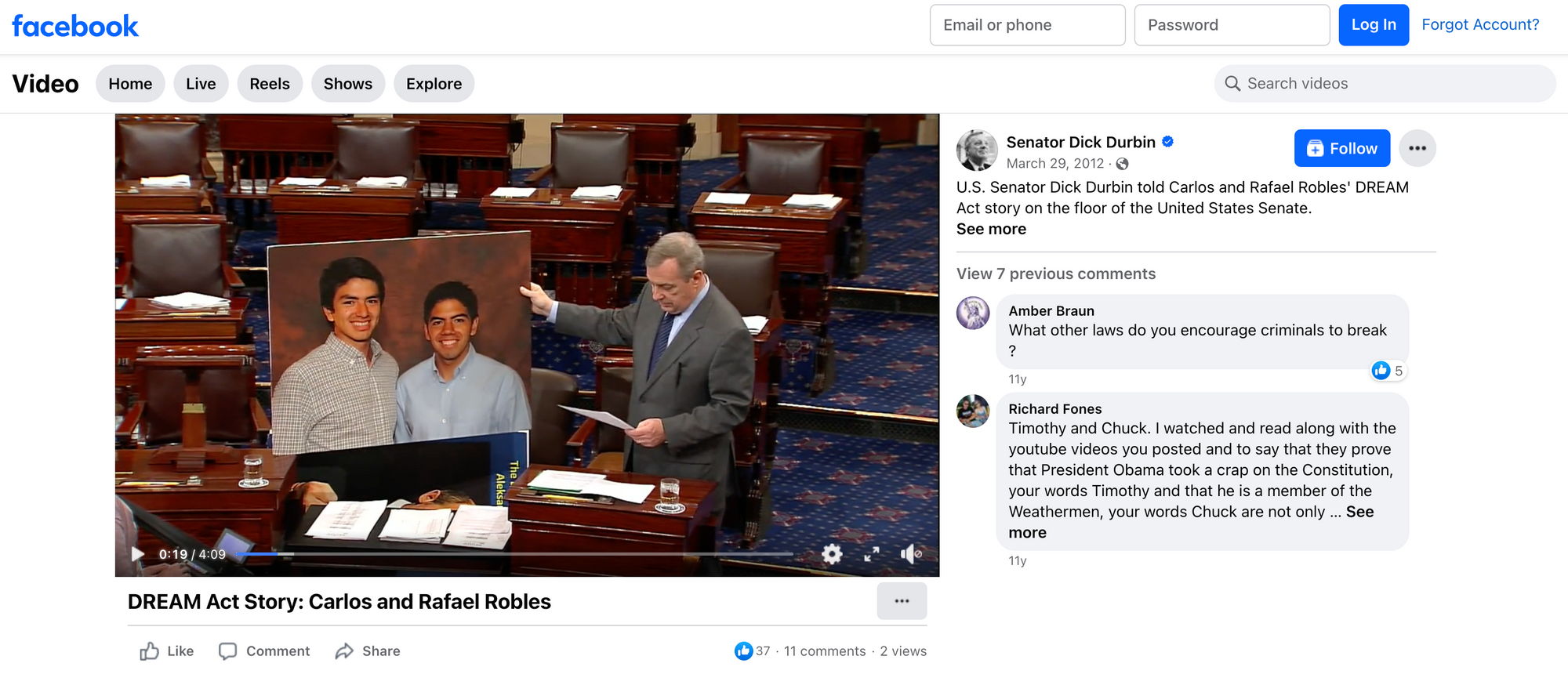

However, border patrol got on the train. We got stopped, arrested, and put in a county jail in New York. We had been in the US for six years, playing by the rules the best we could, doing everything we were told to do that would manifest the American Dream. At this point we were like, “Holy shit. We are at risk of getting deported.” It was Rafa’s birthday then. They sang us happy birthday in jail and gave us delicious Kool-Aid. I hadn't had Kool-Aid in so long! And suddenly, we were poster children for the DREAM Act. Everyone read about these two kids from Palatine, captains of the tennis team traveling to Harvard and getting arrested – a portrait of the people the DREAM Act is supposed to help.

We both studied different things, but came together to work on Duo, our innovation studio/lab. We work on built environment innovations for the benefit of society – we don’t just innovate for shits and giggles. I had studied education, and taught both in the suburbs and in the city, where I saw how our opportunities would have been different if we had stayed in Chicago Public Schools. I was teaching goofy, smart, creative 17 year-olds in both places, but I knew the suburban kids would go corporate while the kids in the city would be working for those guys. It’s bullshit.

Because immigration policies were dictating our lives, I studied for a Master’s in Policy, which got me thinking about systems. I got hard skills in finance while working at Deloitte. There’s the mantra of “never enough funding,” but you look around and all you see is skyscrapers. There is funding everywhere in the United States of America. People pay consultants $250,000 for an eight week report! So there is money, but how are we spending it?

Rafa and I were having these conversations. His background is in architecture and design – being an architect in Mexico is like being a doctor or lawyer in the United States.

Rafa:

I studied architecture at University of Illinois, Chicago. The program is super theoretical: “What is a building?” Some people had a hard time getting a job after a program like that, but I liked it – I learned how to think.

Carlos:

Duo was inspired by the application of architecture and policy thought to the art of creating solutions. Now Rafa says he doesn’t like the idea of “solving a problem.” When you solve a problem, it is usually within the system that exists so the system remains; you’re just patching up a broken machine. The question is, “How do you create new realities?” Architects will also say, “Form follows function,” but who is designing the function? Politicians, corporates, and policy types. How do we design better functions? This is how Duo got legs.

Rafa:

I have a gut feeling we are going to change the way real estate development is done in the U.S. We have enough ability to say, “Fuck it. Let’s make this weird thing people don’t understand at first.” We keep explaining and doing and then people start to see it, then feel it.

I'm often annoyed by the notion in progressive circles that we need to “unlearn” our systems. How do you unlearn anything? You can’t unlearn math. You can’t unlearn reading. If anything, you have to learn something new to act in a new way – which is even more difficult. Unlearning feels like a cop-out.

Lots of folks say, “How are we gonna change? We don’t have power! We need to convince people in power!” At a certain point we said, “Fuck it. Let’s just become the people with the power of choice instead of constantly convincing someone to do the right thing.”

So that’s Duo. We want to set new precedents. We also know how things work in older institutions in order to actually do things in a new way.

Being DREAM Act poster kids informs this. At the time, we did a lot of press: LA Times, Chicago Tribune, NPR. Sharing our story helped us process it, find power in it, like “Fuck yeah! We’re immigrants!” We got invites that exposed us to a lot of major institutions. We were at an event hosted by the National Immigrant Justice Center. They were awarding someone for a building designed by Studio Gang Architects – which is a magical, big deal firm. My sister told me to adjust my speech at this event to tip off that I studied architecture. Who knows, maybe they’d hook me up with a job. The plan worked. I got the internship. I worked hard, which I learned from my dad’s work in the restaurant business and my mom’s work at a factory. Later, my parents started a car dealership and mechanic shop. The juxtaposition jarred me: I worked at this worldly, fancy firm and came home to Mexican mechanics.

While working at Studio Gang, I wondered where all these building requests came from – museums, tower competitions, cool shit. We operated blindly on the requests: the client wanted a tower, we designed a bad-ass tower. But I wondered, “Why does the client want a tower?” I remember meeting with a big Chinese conglomerate who said, “This tower needs to be X-stories tall because it’s the crown jewel for the family.” Being in that room was fucking cool, but also I was thinking, “That is so cringy! They want the tallest tower!? Why?” Nobody questioned the request.

I left the firm wanting to know where these requests were coming from. My first instinct was to analyze real estate – so I got a broker’s license. I started working in sales, not development. Sales is not like Studio Gang – some kind of cultured, NPR-listening crowd. Sales is brokers with a shit ton of money wearing Gucci loafers. I worked for Berkshire Hathaway and later, Sotheby’s – always the most known brands. Again, imbibing the propaganda.

Soon I was working in new construction sales, given my background. I met a developer who asked me why I was in sales, which led to a job in development. Development was another world – lots of wealthy men talking about conquering neighborhoods. It can be super cringe… I remember a conference rewarding a developer for being the first to put granite countertops in units.

If I may interject, both of you really drank the American Dream Kool-Aid – you both got the coolest jobs with the biggest names. Captains of the tennis team, Deloitte, Sotheby’s, Berkshire Hathaway. But at every step you’re like, “This is fucking cringe.”

Rafa:

Yeah, exactly. America can be cringey sometimes.

I needed stimulation – some of these fields felt so uninspired. Then, Carlos had this glorious moment in this movie of our lives. He was at Deloitte, gets off on the wrong elevator floor, sees a sign for some company called “Doblin” and looks it up.

Carlos:

I was working in transfer pricing at Deloitte. Transfer pricing is this ridiculous thing that shouldn't exist – basically companies selling stuff to themselves, but in another country to lower their taxes. I was working on a merger and there wasn’t a printer big enough on my floor to print out their org chart. So I went to a special floor that was like a greenhouse, with high ceilings and windows. Doblin, a really cool human centered design and strategy practice within Deloitte, was on the floor. I told Rafa to apply.

Rafa:

The recruiter, this amazing black woman, told me how to apply with my nontraditional background. Doblin is like IDEO or Frog, firms that do design thinking work. I got a job there, helping companies launch new products and services. Carlos and I had already started Duo part-time, but working with Doblin really helped cement the skill set. This February, I left to work on Duo full-time with Carlos.

What is one project that you’re super proud of at Duo?

Rafa:

Creating Duo itself. We came up with the term “multi-contextual design” which exemplifies our story, given that we’ve been in so many different contexts: small business, inner city life, Palatine High School, Mexico, immigration, policy, design, Studio Gang.

You can design in a vacuum, but then you design some pretty stupid stuff. We try to merge different contexts to create new realities that are beneficial to people. Duo is a machine for ideas, a machine for self-expression. The way we describe it sounds like how people describe art.

Carlos:

I would say that my favorite building project is Starling, a space for liberation.

Rafa:

Right now, we're designing a building in North Lawndale, which is the picture perfect neighborhood of disinvestment in America, racism, redlining and white flight. We're building a new type of building, we think.

It's going to be the first building in Chicago that offers shares of ownership to residents of the neighborhood directly. In the process of doing this, we’ve connected with a lot of people and organizations in the neighborhood, inviting them to be in the room and provide perspective – a new precedent. The building isn’t built yet, but when it is, it will be our album drop.

LIFESTYLE

What is your favorite thing made in America?

Rafa:

Mmm – what is made here?

Carlos:

I love my car, but it's a Honda.

Rafa:

My car is German. Made in America...

Carlos:

Nike's. Well, they're not made in the United States.

The brand is made here.

Rafa:

My Apple computer. I like Apple stuff.

Designed in California, made in China.

Rafa:

This should be a multiple choice question. What is made in America? Not bananas. Not even avocados.

There’s some California avocados, but yea those are mostly in Mexico.

Carlos:

I'm going to go with Nike shoes, because my Razor computer was made in Singapore.

Truly multi-contextualists, you are some of the first people Inventoried to problematize “Made in America.” You focus on the brand, not the product itself.

Carlos:

Side note, I really like the term “United States” because America, to me, is the continent. “America” is something the US wants to call itself.

…I guess my kid was made here.

Rafa:

Same.

CRAFT

For each of you, what is your craft and what medium do you work in?

Carlos:

Well, I joke that my medium is Excel as of late. Sometimes coming up with something cool means it’s a pricing model… and no one wants to touch that with a ten foot pole. I think my craft is transforming things, thinking deeply about things, and like you said, problematizing even little questions. That is part of the charm of Duo.

Rafa:

I draw. If I may be pedantic, I would consider Duo as a conceptual art studio because we rethink things to an annoying point.

I practice conceptual thinking. The people I really like are designers, artists, and architects who are conceptual thinkers. The medium is whatever it needs to be for that concept to come alive. My work is so much stronger with Carlos because sometimes to come alive, the medium needs to be a spreadsheet, or a policy, or a persuasion!

Do you ever have recurring conflict or tension because you think differently?

Rafa:

We have different backgrounds that propagandized us differently. Architects are publicity panderers, no offense. They love to be on the cover of a magazine–they want to be seen. Policy people are behind the scenes. They rarely get a New York Times front cover. Architects have buildings and objects, things that can be seen. So sometimes I’ll have an instinct to let everyone know when we do something. Carlos will ask, “What’s the point?”

Our tensions actually make us more intentional about what we do. Sometimes you need to make art for seemingly no reason, but sometimes you need to find intention behind that. I think that's the kind of tension that we make productive.

IDENTITY

Do you think as an I or as a we

Carlos:

A we.

Rafa:

Yeah, I think as a we.

I didn't even know Carlos would be on the call today. You are like twins. How do you structure your days?

Rafa:

We’ve been very intentional about structuring time around the lifestyle we want to have. Carlos is insistent we leave hustle culture behind. When I left Deloitte, I was working a lot but I just wanted to make art and think. Now, on Mondays and Wednesdays we do what we call “Design Jazz.” We feel like creativity kind of manifests like jazz does. Musicians have a key to the universe – they’re expected to self express, which is a cool thing.

Is it like you two together in a physical space? With other collaborators? A “Jazz ensemble?”

Carlos:

Everyone is welcome and we invite people to come. The other day we invited a guy who had a background in private equity and investment. We asked him to take a look at an Excel – did it actually work? Suddenly, we were doing user experience stuff together.

Rafa:

We’ve had artists come too. One thing we are trying to formalize about our work, which is cool, is that our process is an avenue people can attach to and self-express together. It produces this idea of collective expression.

There was a time when I subscribed to the idea of the sole-practitioner genius. Yet when I worked with those geniuses, I asked, “Why are we doing all the work and you’re in the magazine?” With our process, there is a lot of creative production, lots of people, more collective, more play. We should document it.

SPIRITUALITY

In the words of Leo Strauss, progress or return?

Rafa:

Progress.

Carlos:

What does return mean? Like you returned to where you came from?

Rafa:

Classic. You ask a question, I jump in with an answer, then Carlos is like “The fuck does that mean?” But go ahead.

I approach it as a spiritual tension: moving ahead to become better or returning to some kind of source, energy, tradition… even “Make America Great Again.”

Carlos:

In that sense, a little bit of both. You don’t want to go back… kind of like our immigration story. I wouldn’t go back to Mexico. I also like progress, but not for its own sake. You have to serve your purpose.

Are your neighbors worthy of your love?

Carlos:

Yeah?

Rafa:

I don't even know my neighbors. Well maybe one.

Carlos:

I think anybody is worthy of love.

You two, despite being very conceptual, you’re also in the world, very tactical. There is a materiality to your answers.

Rafa:

That's a compliment.

MEANING

What games are you playing and what games are being played on you?

Carlos:

I think the bank is playing games on me all the time and money is playing a game on me all the time, trying to not let me live my life just how I want. Games I’m playing? Literally, The Legend of Zelda on the switch. Games of life? Navigating neoliberalism. That is a game.

Rafa:

I feel like I'm playing Jenga. You poke a piece and then you're like, take that! Sometimes we want to be like, “Fuck you bank!” and pull the whole tower down and then make them rebuild their own thing! The game being played on me? I mean, this immigration shit is crazy. It is also an intentional one. There is this facade, like, “Oh man! You’re so American! We have to help you, you got to be here!” But then nobody does anything about it, not on any political side.

Carlos:

The system is not broken. It was made to be a fucking pain in the ass.

KNOWING

Is there something you know that you wish everyone knew?

Carlos:

That money is made up.

You’ve mentioned money, banks and neoliberalism. Can you unpack that?

Carlos:

There is a notion that money is a helpful tool. Money is older than capitalism! The way that we use it now is just so dumb. For example, our Starling project: it will take six months to get built, but the hardest part is getting access to a loan to build it.The tangible thing is ready to go, but the intangible thing is holding it up!

Rafa:

I want people to know that everything is constructed and it can't be deconstructed. There is this notion you can change the banking system. But you can’t do so easily: it’s incredibly problematic, protected, and strategically segregated. You’re not going to change that. But what you can do is construct, because everything is constructed. You can create new realities by designing new things, designing alternative models, finding alternative people, giving people the mic who haven’t had a chance to say something. You can do that. There is this whole movement of dismantle this, dismantle that. You will lose, completely. You have to operate differently by building differently.

AMERICA

What is an American dream? And what is an American nightmare?

Rafa:

Mm-hmm.

Do you guys identify as American now?

Carlos:

Yes, in the broad continental definition, I would say.

One thing I like in the narrative of Mexican immigration is that people used to say, “Ni de aquí, ni de allá” (neither from here nor there), but now people say “De aquí y de allá” (from here and there). You’re both. I really vibe with that.

Rafa:

Cornel West described himself as a multi-contextual intellectual. That vibes with us because we are all the different contexts we inhabit. I’m Mexican, and I’m American, and I’m all my professions: architect, designer, artist. At a certain point, why talk about identity anyway? Who you are is so many things.

I think about it in terms of how people experience conceptual art. Some people go to a museum and ask “What is that?” Just experience it. I feel that way about people. Just experience people. Don’t try to figure out who they are. Just let people unravel. If you vibe with them, keep going. If you don’t, turn around.

In terms of American identity, did you have a vision of what that was? Did you want it?

Carlos:

I remember not wanting to lose my Spanish. I wanted to be part of everything of course: intramurals, all of the high school stuff. But language was a huge part of my identity that was non-negotiable. Food? Well, our grandma came eight months later and started cooking for us. So we could maintain food and language. Fashion wise, we already wore American brands in Mexico: Abercrombie, Aeropostale, clothes aligned with White culture.

Is there still an American dream for you? Or was some kind of wool pulled from your eyes?

Carlos:

You can make it happen here, but it's not a feature of the system by any means. The American Dream was “Middle-Class America” after World War 2. You do these things, get your house, your car, your kids. You play by the rules and you’re going to get it. It seemed like a project everyone had access to, which wasn’t true. Not everyone had access. That type of American Dream I definitely don’t believe in.

But then there is a personal life dream. I think you can make it happen here and in similar industrialized countries. I don’t know that I would be as happy in Mexico given the things we were able to build here. I also wouldn’t want to move to another country – why do that again? I’m happy here with what we build. We know how to navigate the thing. I’m not drinking the Kool-Aid at this point. I feel more in control of how I can shape my own version of the American dream.

Rafa:

The veil was lifted on the media-created American dream. Our immigration experience shaped that a lot. We met a lot of other people who assimilated super hard.

But the cool thing about the United States, the “red-white-and-blue” flag type vibe is that there is freedom of expression vibes here. Chicago is a very progressive place. We can do Duo here. We can make up our own explanations. We also find a lot of inspiration in American thinkers, especially Black American thinkers.

When I started in architecture, we didn’t study any Latin American architects. I didn’t even think about that until later, when I was like, “What the fuck? I don’t know any names from Latin America!” I didn’t know anything about the assets or minds or systems or proportions. It was all from the Greeks and the Le Corbusiers.

So I went on a deep dive to reference all these other people. But even in their writing and thoughts, they were referencing or emulating the United States in a way. Here is the epicenter of a lot of cultural movements and norms that then move outward into places like Mexico. If you’re in it, you can see the bullshit. I’ve had Mexican friends come visit, talking about something that was big five years ago here but is new there.

YOUR PEOPLE

Who are your people?

Carlos:

Rafa, my wife, my son, our family. Rafa’s wife and daughter. If shit hits the fan: family first.

Rafa:

I agree. Professionally, our people are types who stopped believing in certain American ideals as they are showcased in classic media – lots of artists, people who think on their own. But if a supervolcano erupted, I would save my family first.

That feels like the most United States American slash Mexican thing to say.

Rafa:

Fast and Furious!

As they say, “faith, family, freedom!”

Rafa:

I would say family, freedom and faith.

Because we were one of the first people, if not the first people, to receive DACA, we have gotten the chance to talk to a lot of people across the political spectrum. When we’re lumped into the masses, that is the only time I’ve seen some kind of showcase of outward racism. Anytime I have a conversation, even with very conservative people on a person-to-person basis, they’re always like, “Whoa! Your story is crazy! That should not be happening! How can that be? That’s not America! That’s not what we’re about!”

I’ve always thought that is really interesting because when you think of propaganda, of mass media, oftentimes it says, “Deport them all! Build a Wall!” Lots of people aren’t thinking critically about how this wall is impractical. Or how deporting everybody isn’t going to happen. Even when we were detained, the officers in the jail would say, “You speak better English than my kids.” That was a weird one.

Carlos:

But speaking of America and the flag. There is something I liked from Nicole Hannah Jones in the 1619 Project. Her dad was a Black veteran who got the short end of the stick coming home. He fought for the country, and even when he wasn’t afforded all the same things as other soldiers, he wouldn’t get rid of the flag he hung outside his house.

She goes on to talk about the reason we have public education, free health clinics and jazz: the contributions of Black people and immigrants. Some of the best things about the United States are appropriated. They come from people not deemed American. But this flag is their flag too, and their contributions made the flag what it is. That’s a cool thing.

I feel weird about the flag sometimes, but I think it should be recaptured. A recaptured symbol is even stronger than a new one. If we recaptured it, maybe people would know more about the foundations of that flag as opposed to the people currently wearing it…